Urban Block-Buster

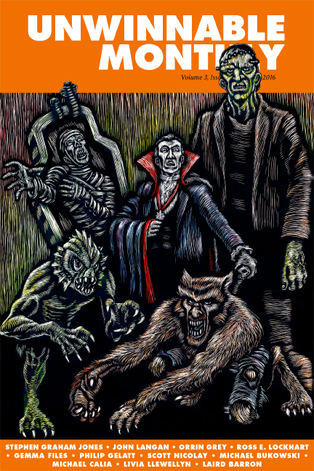

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #84, the Monsters issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #84, the Monsters issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

I’m not sure why we, as a culture, enjoy watching the destruction of urban life in blockbuster films. I know that I, as a person, have become more and more uncomfortable with the experience as each year’s set of summer action films hits the market. With 2015’s Avengers: Age of Ultron, I could feel myself become desensitized to the violence as the film played. I felt squeamish and anxious during the gigantic downtown battle in the film’s first act, but by the even grander set piece in the film’s climax, I was just exhausted and numb to the violence on-screen, my brain no longer protesting the unquantifiable damage being done. This is disconcerting.

Age of Ultron makes a point of showing the film’s heroes saving civilians from death as they obliterate their livelihoods, and protecting innocent life is a major subplot in the film’s finale. It goes so far as to state that the Avengers will not tolerate a single human death and depicts the ensemble scrambling through the wreckage to save every endangered life as evidence of this motivation. As a result, I’ve heard it discussed as a much more responsible film than its peers, which often disregard the collateral damage they create. While I appreciate, to some degree, the film’s efforts, they ultimately feel disingenuous.

The idea that every life can be saved in this kind of situation is not only absurd, it’s insulting to the audience. It’s a way for the film to have its cake and eat it, too; we get the visual catastrophe that the filmmakers want us to see without any of the guilt or ethical hand-wringing (for either the audience or the heroes). No matter how many jump cuts there are to costumed protagonists catching civilians falling to their death or loading them onto an escape vehicle for safe extraction, the numbers simply don’t work. What is out of the frame is often as important as what’s in it. The film only pays lip service to the idea of accountability.

During the first major confrontation in a city, Tony Stark flies over the scene, searching hastily for a place to dispense of his opponent that won’t lead to civilian deaths. He finds an under-construction skyscraper and discovers that it’s unoccupied and therefore fit for demolition. As the building collapses, we watch the montage, familiar as it is from Hollywood and news coverage: the windows erupting, the people cowering with their hands over their heads, the enormous clouds of dust consuming the streets as the crowds try, in vain, to outrun them. Stark has succeeded in finding an empty building to destroy (and accompanies his success with a trademark quip), but the film has resolutely ignored the fact that the definition of “casualty” includes not just lives ended but lives compromised and displaced.

In actuality, the concern is not for the people affected by this destruction. Their devastation plays as a means of reminding the audience of the upstanding moral code of the leading cast. The crowds act as a shortcut for character development. They are props. They’re a cheap way to raise the stakes without having to commit to placing lead characters in any meaningful danger that might risk their involvement in the next saga of films in a moneyed franchise.

The cities are largely anonymous, barely named or depicted outside of their purpose as a backdrop for carnage. The film never returns to the two sites of urban destruction in its first half, proving that its sense of responsibility is fleeting and opportunistic. Once the fight is over, so is the film’s ethical obligation. Whatever happens after the dust settles is not our concern, apparently.

The public’s anger over the violence set upon their lives becomes a plot point in the second act, pushing the heroes into hiding as they restrategize and address personal problems. Again, the perspective is telling. The audience is never expected to sympathize with those whose lives have been deemed peripheral; we are expected to believe that the heroes’ struggles for justice are worthy and that they will, eventually, find a way to convince the world of the same. We are not supposed to experience the same outrage that the rest of the population does.

Batman Begins made efforts to address these issues back in 2005 by developing the city of Gotham into a sort of character of its own, incorporating the town’s politics, economy and people into the fabric of the narrative more thoroughly. This comes with its own host of problems – it’s best not to even mention the film’s sequels for now – and the audience is still witness to brutal environmental and personal violence. If there is a benefit to this approach, though, it’s that the violence feels more severe and therefore is considered more seriously by the audience. Batman will still plow through neighborhoods in a tank, but if the film has done its job properly (which is debatable), the audience will better understand the gravity of that choice and its effect on both the hero and the community.

The ‘90’s anime series Dragon Ball Z, made primarily for an assumed audience of ten-year-old boys, had a different approach. Once the confrontations get serious, the fighters almost always relocate to some desolate battleground in the middle of nowhere. Some endless stretch of desert or mountains surrounds the cast as they kill each other, leading to dozens of hours of fights that have no visible impact on civilian life but exist only in reference to tracts of bland yellow or green or blue. Over the course of almost 300 episodes, it becomes a ridiculous, formulaic solution and unquestionably boring, but if we aren’t willing to seriously consider the repercussions of the violence we encourage on-screen, at a cost of $200 million per film, then maybe boring is what we deserve.