Poems For Fingers

It’s strange but undeniable that for all the millions we’ve spent on creating and consuming videogames over the last 20 years, we lack any broad clarity on what they are or quite why they have won their space in the sun. Never before has so much been spent on something so little understood.

Games don’t help themselves. Even beyond the perpetual violence and shooting galleries, videogames pursue a cycle of incrementally improving visual and mechanic prowess as if they were the next family hatchback. The waters are further muddied by an appetite to drape filmic direction and bookish storytelling over and around their interactive core –obscuring any remaining distinctive moments.

The players don’t help either. Any ascent to videogame maturity and value for grown-ups is eclipsed by the lion’s share of purchases falling to the yearly updated derivative Hollywood-styled FPSes. The boxes at the top of in-store sales charts drown out any pretense that this is anything more than a gun (or zombie) show.

If the reality is different to these unintended messages – and it certainly is – the challenge for all involved in making, playing and writing about games is to jolt the conversation back on track. Analogy is inevitable but inevitably falls short.

Playing games is like a book club which has shared an unusual and surprising read, but without the social acceptance of novels. The act is like finding the time to fit theatrical performances into busy lives, as theatergoers are wont to do, but without the sense of worth and self improvement. Players are like film fanatics on opening night, but without the easy accessibility and understandable stories.

Playing games is like a book club which has shared an unusual and surprising read, but without the social acceptance of novels. The act is like finding the time to fit theatrical performances into busy lives, as theatergoers are wont to do, but without the sense of worth and self improvement. Players are like film fanatics on opening night, but without the easy accessibility and understandable stories.

There is truth in all those, but they don’t ring true. Games may dance around literature, theater and films but only in the same way a child incorporates its surroundings into imaginary play. We get transfixed describing the mechanics of the invented game and rarely consider how it functions in the child’s life.

Videogames may have mechanical similarities to books, theater and films but they function like poetry. Not that they rhyme or follow syncopated structure, or have that kind of cultural equity. Nor are they are the preserve of the middle classes. Or even hard to understand to the uninitiated.

Games are like poems because they create worlds latent with meaning, but then guard these experiences, demanding time and investment to enjoy them. Like poems, videogames need breathing space to be understood. They take time and need dedication. To rush through to the end, to only solve them, is to leave with half the story. Give them time and they will surprise you with unexpected moments of enjoyment and unasked-for connections to life.

Games are like poems because they become our friends, staying with us long after we’ve finished playing. To discover a new favorite game is like that treasured encounter with a poem that promises to become a lifelong soulmate. The same heady thrill of encounter, the same fear that it won’t last; games hold within them potential for long-term companionship.

They also invite us to overhear life’s questions rather than doling out answers. Unlike books and films, with their embattled defense of authorial intent, games are inescapably porous. Meaning is negotiated between reader-player and invented world. Despite appearances, like poems, games are gentle story carriers.

I was struck by this when first listening to a song by Rebecca Mayes written in response to thatgamecompany’s Flower. Playing the game enabled her to “know now what it’s like to dream as a flower would,” to “write a symphony with her fingertips”. Addressing the game, she commands us to “take our time” so we might be able to “bear the weight of this poem”.

Of course there are differences. Poems knock at the eyes and memory, whereas videogames come calling at the tips of our fingers. Players are called to creation with their interactions rather than memory – but both, by these different entrances into the body, make worlds in every sense of the word.

It’s no mistake, or bad thing, that controllers have so many buttons inviting ever more interactions. It’s more significant than we might assume that Xbox One’s Kinect can now detect in detail our digits (and not just our limbs). And the haptic feedback present in the triggers of the new controller is a game changer in waiting, sending ripples of sensation back into our fingers.

I came across this prose on Anthony Wilson’s blog (Love For Now) about the experience of finding a new poem. It encapsulates my experience with videogames better than anything else I’ve read, despite being explicitly about poetry:

Sideswiped by poetry

And sometimes you don’t know where it comes from.

It appears as a heat, prickly, under your skin, your scalp.

You open a book and find it there pulsing, on a page where it wasn’t before, by a person whose name you do not recognize.

It appears to have been lying in wait for you, for just this precise moment of tiredness and openness.

It is like an accident, a jar falling to the floor, a bump in the car, as we say in slow motion.

Somewhere below your belt your insides shift a bit. They gurgle.

You realize you are muttering the words under your breath, like a woman you saw in a waiting room once.

You hope no one walks in and catches you.

You go to the internet. There is nothing to be found about the poem there, nor its author.

You go back to trying to trust the thing in front of you, double-checking the spine of the book for signs of tampering.

You mention it to no one.

You think you may have fallen in love.

You have to go out. You hope the poem will still be there when you get back. You half believe it won’t be.

You mention it to no one.

Until now.

We are used to reserving this kind of talk for more important areas of life; the ancient, the worthy, the tested – just not something as new, harsh or commercial as a videogame. But this category, this description, gets closest to describing how games function in discovery, play and memory.

We are used to reserving this kind of talk for more important areas of life; the ancient, the worthy, the tested – just not something as new, harsh or commercial as a videogame. But this category, this description, gets closest to describing how games function in discovery, play and memory.

But to re-describe – to re-categorize – videogames in this way we first need to come clean. Addressing videogames as poetry, or indeed as any kind of art, is to talk today about a possible future for games that has not wholly arrived.

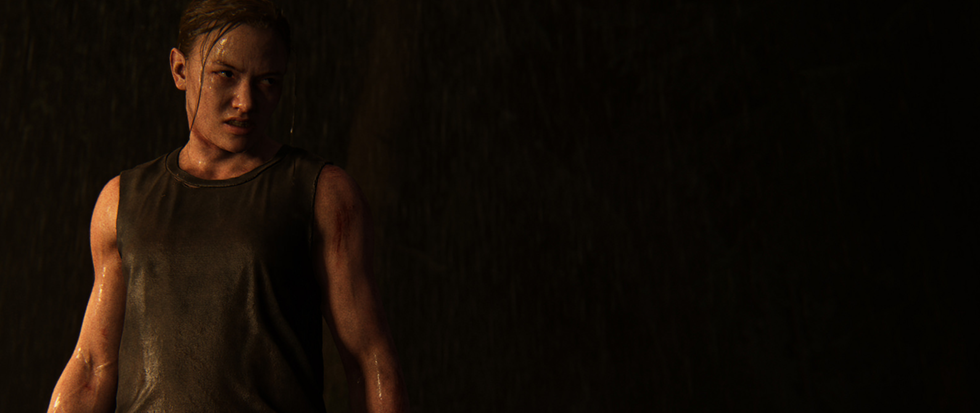

It is to imagine games like The Last of Us being able to leave the killing behind for a prolonged period if Neil Druckman so wished. It is to imagine games like Beyond: Two Souls without the schizophrenic pull of Hollywood impacting David Cage’s writing and direction. It is to imagine the green shoots of a hundred indie games, like Flower and fully grown and on the red carpet.

That day is not today, but how we talk about games now will affect what that day looks like and how it soon will arrive. Until then these poems for our fingertips continue to stir and move and entertain those of us reaching out to touch their world.

———

Andy Robertson is a freelance family gaming expert for the BBC and runs Family Gamer TV’s Skylanders coverage. Follow him on Twitter @geekdadgamer.