The Leisure of Light Obsession & No Man’s Sky

My mom, like most moms I assume, has had various phases of collecting in her life. For the longest stretch it was strawberries: find mom something nice with strawberries on it for her birthday, you know how it goes. From there the motif morphed from moose to anything with the word “joy” on it, to the current focus: wine. She collects, is gifted, and purchases a lot of this junk, and I admonish her every time I visit about how these collections fill her home (possibly too much—sorry mom!), stuffing the corners and holding down the table. There’s no finishing line or reason why one theme suddenly usurps the other, just a few keywords to highlight while strolling through the outlet shops and flea markets, for friends to find and bestow as a way of saying “here, I thought of you.”

We all do this to some degree, despite current tiny home fads and trends in extreme minimalist lifestyles. I’m buried with guilt by books read and unread, records haphazardly purchased at shows and while travelling, Steam games, etc., so I’m a bit of a hypocritical son. It’s the spectre of capitalist consumerism looming large over a more naturalistic instinct to collect, to nest, to surround ourselves with the familiar, but also to know, to amass a personal body of knowledge. To become, if not the expert on a subject, at least something of an expert, in order to ponder and pontificate on as a form of leisure or light obsession.

I saw Fredrik Sjöberg speak on collecting hoverflies, the basis of his memoir The Fly Trap, at the joint MIT-Harvard Ig Nobel awards last year. His speech and book are not just about collecting hoverflies, but the nature of collecting in general, and much more than that. Sjöberg became the foremost expert of one insect that pretends to be another on a small Swedish island, and even then, would never complete his investigation of even this limited landmass. There are just too many flies, too many variations in size and behavior and every physical trait; a solitary island becomes an entire planet or solar system by scale.

One of the most compelling tributaries of the many winding through The Fly Trap is Sjöberg’s ruminations of “buttonology,” a term coined by August Strindberg: “But because the idle found it difficult to do nothing, they invented every sort of idiotic foolishness. One began to collect buttons; a second gathered spruce, pine and juniper cones; a third procured a grant for travelling the world.” Sjöberg insists that Strindberg was taking a shotgun approach with this insult, but most definitely included scientists and entomologists in his sights, though Sjöberg conjures some history to make a case for the intimate knowledge of maggots against accusations of subpar housecleaning. “You never know in advance what knowledge may be good for, however useless it may seem.” Maybe we are only ever called to action once, that single shot at the brass ring, but we best be prepared when the call comes.

Then again, sometimes it’s enough to just be aware of our world once in a while: “There is a day in April when the southern sun opens the buds on the earliest sallows, and on that day the first hoverlies appear. Tiny, uprepossessing species that the books often describe as rarities, perhaps because they really are quite rare, but more probably because no one sees them.”

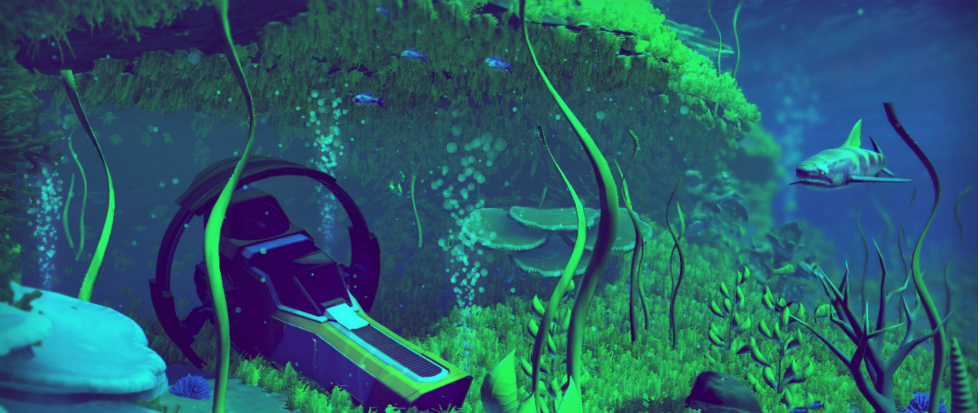

This attitude towards collecting possesses me while meandering through the alternate-reality space of No Man’s Sky, one of the most misappropriately maligned games of this generation. This title promised something new, which the breathless hordes took to mean as a promise of everything new, an entire galaxy built on math and wonder, who then gnashed their beaks in rage when the limitations of code and a small team dared to deliver something less than the invention of the holodeck.

Their loss, as No Man’s Sky offers a fantastic island for videogame buttonology and has only expanded in the year since its release. Infinite flora and fauna exists to be hunted or stumbled upon, and there’s a meditative peach to be found skipping from planet to planet to find the widest variety possible or hunkering down and mapping out the squiggliest caverns and chasing the shadows of what glides overhead. Not unlike buttons, which by the nature of their utilitarian task differ mostly by degree, spending time in No Man’s Sky will more often present a sense of deja vu when spying new species. To the endlessly curious buttonologist it’s that degree of difference where an intimate knowledge truly shines.

Many games hope to offer tens of hours of playtime, along with achievements, trophies, easter eggs, discoverable tchotchkes that don’t affect the gameplay, and perhaps a compelling narrative, but No Man’s Sky delivers decades. But at this point our imaginations still outpace the processing power of algorithms and consoles, so it’s understandable why some were let down in the delivery. The game just got its third update since launch, adding more biomes, vehicles, story, and the possibility of running into a kind of willowy spirit avatar of another player in the same slice of space as you at that single moment.

Time will tell if this is the final update that brings the game up to the speed many thought it would hit the ground running, but the buttonologist in me has been happy with this one from the start. I’ve been content to hole up or wander a world to watch its minute splendors unfold, and now I have more to explore. Playing No Man’s Sky does not belie the use of one’s imagination, however. There’s a story behind each discovery, and collecting planets, pets, or plants throughout this universe can provide a kind of peace as we fumble through our chaotic existence, gathering buttons all along the way.

Header Image is Hoverfly Face by Martin Cooper, used under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0.