On Short Night of Glass Dolls

Giallo film was a cycle of Italian murder-mysteries that flourished for a few decades in the mid-20th century. Giallology is a humble appreciation of these movies.

———

1971’s Short Night of Glass Dolls is a sedate giallo without a murderer. Director Aldo Lado, making his debut, and cowriter Ernesto Gastaldi, a genre fixture, diffuse the black-gloved killer into the entire ruling class of repressive Soviet Prague.

Glass Dolls stars Jean Sorel (Belle de Jour), doing his best Franco Nero, Ingrid Thulin (Cries and Whispers), and Barbara Bach (The Black Belly of the Tarantula). The score, as ever, is by Ennio Morricone and the Techniscope cinematography by Giuseppe Ruzzolini (What?).

In most every respect this is an unusual giallo. American Gregory Moore (Sorel) is a journalist looking for his missing girlfriend Mira (Bach), but he spends most of the film’s present tense paralyzed. In the first scene a groundskeeper finds him, seemingly dead, after a crow alights on his body. He’s taken to the morgue, destined for the autopsy table. The meat of the story is told in flashbacks with Moore’s voiceover, giving the device of the protagonist’s buried or repressed memories a twist. Only one murder happens onscreen; a string of disappearances is referenced but kept in the background.

Lado and editor Mario Morra cannily intercut between present and past with match and jump cuts that elide large amounts of time, and bridging montages that give us a brief, flickering preview of Moore’s upcoming flashback, like a rush of memories that come all at once. That device may be familiar to anyone who’s seen Nicolas Winding Refn’s 2009 Valhalla Rising. These techniques are subtly used to leave open the possibility introduced late in the film that Moore himself is responsible for Mira’s disappearance.

When the patented giallo psychologist gives his spiel about the killer’s “deep psychic derangement” and seizures during which he wouldn’t remember his actions, the formal language of the film to that point makes us second-guess Moore’s reliability. That said: we don’t second-guess for long, because everything is answered immediately thereafter.

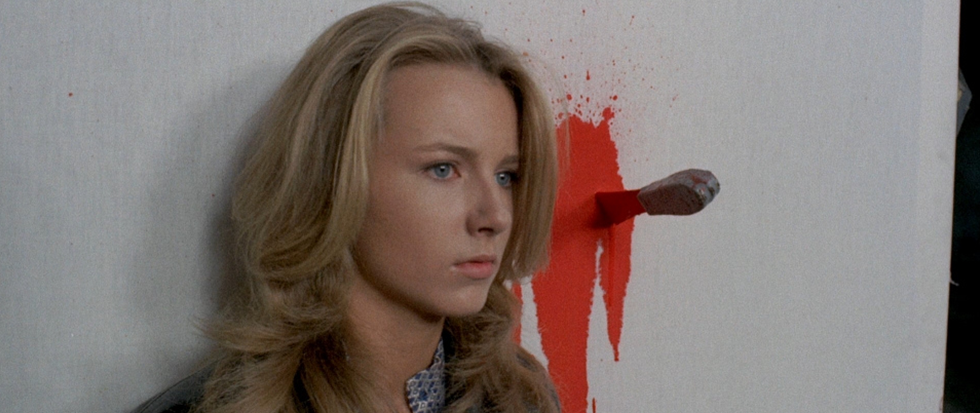

Spoilers ahead: Mira (“peace,” in Slavic languages) fell into the hands of Klub 99, a bizarre black magic cult who use Prague’s youth to sustain their power. The cult is comprised entirely of Prague’s richest, most influential citizens—who happen to have met Mira and Moore previously at a party. There they fawn over her, Ruzzolini placing Mira at the center of his wide frame with socialites crowding her on all sides. The next day, she disappears. Moore eventually stumbles into their ritual and is put into the paralyzed trance we see him in at the start of the film.

The meat of the film takes its time to mount dread and uncertainty, striking a tone somewhere between Roman Polanski’s Apartment Trilogy and Stanley Kubrick’s 1999 Eyes Wide Shut. Lado layers his slender plot with motif on motif like a tinkling chandelier, tropical flowers, butterflies, and one distinctly sinister painting that may or not mirror the climax exactly. Ruzzolini’s photography in the flashbacks is disciplined and rich, full of blackest-black night shooting and vivid interiors—a world of suffocating luxury, like the rotten beauty of a corpse flower. Morricone’s music hangs on an eerie, wispy vocal theme that inflects the film with a horror edge.

The cleverest thing about Short Night of Glass Dolls is how it makes giallo tropes part of Klub 99’s repressive structure of power: the psychiatrist’s wrap-up monologue becomes an attempt to discredit Moore; the obsession with naked women becomes a desire to consume their vitality; the journalist working with the police becomes the police attempting to coerce a confession and prevent further digging.

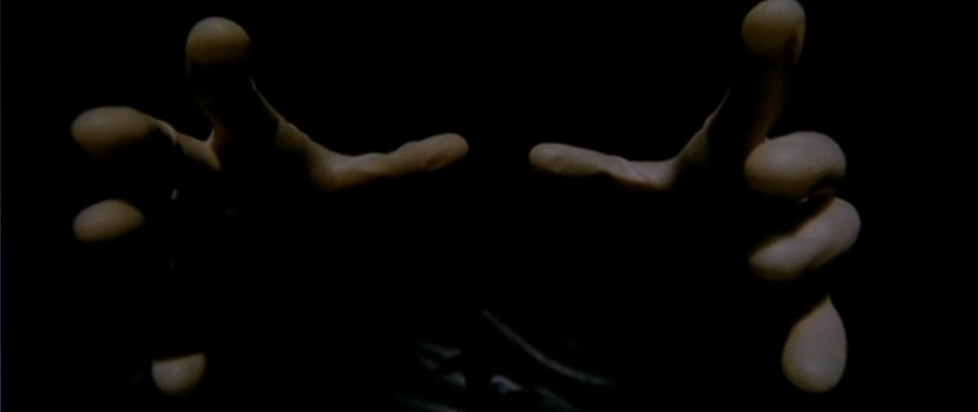

Its nihilistic ending is a brutal illustration of the lengths the ruling class will go to in preserving their power. Moore stirs on the autopsy table, but the doctor—who we suddenly recognize from the cult ritual—clamps his wiggling hand down and slides a scalpel in between his ribs, directly into his heart. The cultists watch from their perch in the operating theater, secure that their reign will continue for as long as there are lives to devour.

The intelligentsia were the engine of the brief, abortive liberalization of 1968’s Prague Spring, after which the Soviets invaded and occupied Czechoslovakia. But the architect of the Prague Spring, Alexander Dub?ek, was a longtime Soviet bureaucrat; hardly a fresh-faced reformer. The vampiric aristocrats of Short Night of Glass Dolls are unnervingly broad in their metaphor—whether the viewer supports, disdains, or has no fucking clue what the Prague Spring was.