Revving the Engine: Wartile

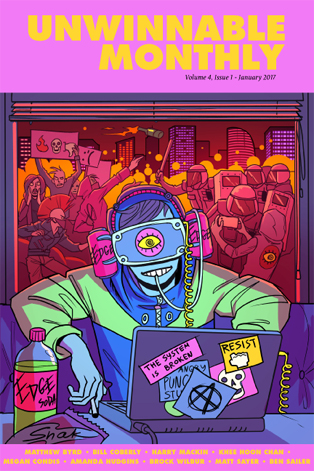

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #87, the Rebellion issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #87, the Rebellion issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

This series of articles is made possible through the generous sponsorship of Epic’s Unreal Engine. While Epic puts us in touch with our subjects, they have no input or approval in the final story.

———

Seeing Wartile inspires a peculiar feeling in me. On the one hand, I want their battle boards, these detailed dioramas of terrain and buildings. I want them in my home. I want friends to gather round them to play elaborate tactical games with miniatures. When I was a kid, these Wartile battle boards existed in my imagination. I wanted to build things like this for my miniatures, but bits of model trains sets and papier-mâché only go so far, especially when you’re eleven.

On the other hand, I know that they can’t be real because to be real would be to rob them of their magic. Miniature soldiers can’t move, resin waves can’t crash, plastic fire can’t flicker. And to play the game in the physical world? A nightmare of calculation, a chaotic whirlwind of bits outstripping the most complicated board game. No, keep these mechanics out of view, in the code. Let me play without reckoning.

In this way, Wartile is indelibly digital and interactive – only in that space can they live, breathe and move – but the allure derives from a want of physicality. Why can’t this be real? Why would I want it to be? In the tension between the two lies the appeal of the game.

Michael Rud Jakobsen, founder of Playwood Games and lead designer of Wartile, was kind enough to chat with us and explore this interplay.

Let’s start off with you. Can you tell me a bit about your history developing games?

Michael Rud Jakobsen: At the Danish Design school, I studied ceramics and glass with a desire to tell stories through shape and material. I started using 3D software to create my early concepts and ended up loving the possibilities the software gave me to quickly produce and iterate ideas. Soon after I made a switch from ceramics to digital design where I started to study game design and visual art for games. We were a few dedicated students who created a mod on the Cryengine named Ultraball, inspired by the old Amiga game Speedball, just in first person view. I believe we were among the first students in Denmark to study and create computer games as part of a higher education. A few years later DADIU (The National Academy of Digital Interactive Entertainment) started, which now it one of the official paths you can take in Denmark if you want to study game development.

After the school, I started to work with Zeitguyz, a small indie studio with high ambitions and lots of passion. There I ended up as Lead artist working both with level design and environment art. Unfortunately, Recoil: Retrograd was cancelled and the team of around 25 developers at that time was laid off.

After Zeitguyz, I started to work at IO-Interactive on the Kane and Lynch 2 production as environment artist and then on Hitman as game designer. It was a great opportunity to work in a highly professional studio and experience how a AAA production was made. You get to work with the best in the industry and everyone around you are experts in their field; the time was very educational. After more than six years with IO-Interactive, I felt the time was right to follow an old dream of mine, to startup a studio of my own.

Was starting the Playwood Games easy? Can you tell me a bit about the rest of your team?

R. J.: When I started the studio, I was very lucky to convince Tom Rethaller, a senior programmer and also a former colleague from IO, to join the project. The scope and plan of execution was smaller at that time but have grown substantial since then. Together we build an early rough playable prototype of Wartile, where we could see the unusual game mechanics.

The first year was very hard as I had to finance everything from my own savings. There was no money to pay salaries, which, in the end, resulted in Tom had to seek opportunities elsewhere to survive. Flexibile is the best way to describe our team structure. As a small surviving studio on a very tight budget not knowing about the financial situation just a few months ahead, it was important for us to build the team with the ability to scale up or down our active work force to only include core development for months if needed.

So, what is Wartile?

Wartile is a real-time strategy game with a turn-base feel. It’s miniature world come to life. Here you bring your collection of figurines to battle on small, beautifully drafted diorama battle boards made in different themes, from the dark foggy swamps, stormy coastlines to the cold snowy mountains.

Wartile is a fantasy universe set in the early medieval period. The first campaign lets you take control of the brutal Scandinavian Vikings as you set out to meet the challenges and opportunities on journey of making a name for yourself.

Its core game mechanic and the phase of the game is very different than from any other game, as every figurine have a cool-down that triggers when it is moved or engage in combat. This result in a real-time flow, but with a strong turn based feel as you move your figurines around the board as you would in a turn-based game, just without the waiting for your next turn.

All your figurines have a life of their own and will complain or compliment your tactical choices and celebrate when winning. Together with unique ability cards for each unit class, the player also has a selection of godly and tactical cards that, if used right, quickly change the course of the battle.

What inspired Wartile?

R. J.: This is a tough question, since I tend to believe that we are by everything that surrounds around us, by the people we meet and all the stuff we see, hear and feel.

The premise of Wartile came from the ambition to recreate the feeling of playing with miniature figurines as a child, building small landscapes and bring it to life by adding personality, voices and actions to those small figurines.

With Wartile we want to build this miniature universe so many remember from their childhood memories, but as a place where we again as adults can go and have fun without the effort of making everything up ourselves.

The tabletop/wargaming diorama aesthetic is beautiful. One of the things I find delightful about Wartile is how much I want to touch the game components. How do you approach designing a game like this to appear so sculptural and physically present?

R. J.: The true miniature feel is a very high priority to us and it’s not something we nailed at day one. It has been a slow and long process with many iterations to get where we are today.

Are there significant differences in creating a simulation of a board game versus a physical board game?

R. J.: Everything is different. With a physical board game, you have a very social interaction between with the other players. You can enjoy each other’s company while waiting for their turns and all game rules and mechanics are visible, to everyone. In a simulated game, you tend to sit alone, even in multiplayer games. The social relationship or level of interactions is very different during the playtime, and the game rules and mechanics can be hidden, depending on the game.

With Wartile, we want to focus on reproducing the feeling of playing a board game and not to simulation one as such. This is what truly set us apart from anything else, but it’s also where we have the hardest time to communicate our vision to our audience.

For that matter, why develop Wartile as a videogame and not a boutique board game?

R. J.: Wartile could not be a board game in its current construction, since it’s a real time strategy game, with a purpose to immolate a living miniature world. Maybe you could make a game that used the same art direction and universe as Wartile, but the game would play and feel very different the moment you made it turn based and static.

It would seem to me that a game like Wartile would be a natural fit for a turn-based game. Can you talk about your decision to make it an RTS and how that effects gameplay and design?

R. J.: We experience a strong desire from parts of our audience to make this a turn-based game, but our ambition has always been to make a real-time game that keep the player active, always with choices to make and without the downtime of waiting for the enemy turn.

With an aim to create a game from the best of two worlds, we designed the cool-down mechanic and iterated from there. In the beginning of the project, we tested out many different visual approaches, from a board made of wood, to landscapes that are more realistic. We ended up with tiles as they very clearly communicated the player’s navigation space and tactical choices. The clear-cut battle board look had a strong visual appeal and showed the limited play space for the level, which was ideal as we wanted each battle board to have around 15-20 minutes of playtime.

Making Wartile turn-based was never really something we truly considered, but we understand that the strong references in our visual art create a desire for us to take that path. On the other hand, we do feel that we are on something new, different and really fun.

Since last year, we have been running play tests among our fans and we are getting a very positive feedback on everything from art to game play, but we also acknowledge that we still need to make many improvements and have a long way to go, before the game will be perfect.

Let’s talk about the card mechanic, which is a natural extension of the tabletop aesthetic. They seem to keep the action very intimate. How do they work and what’s your thinking behind them?

R. J.: From an artistic point of view, the cards enforce the feeling of playing a board game, the way you customize your deck of cards from the menu and then drag them onto the battle board or figurines.

The cards are a simple and fun way of using powers and figurine abilities that easily can change the curse of the battle. It should not just be about movement and position, but also about the choices you make when using the cards available on your hand in the given situation.

What do you hope players take away from Wartile?

R. J.: First of all, a good and enjoyable time. It should give you a moment that is yours where you can take your mind away from reality, into a fantasy universe where different rules and opportunities appear, that both challenge and inspire you.

When pitching Wartile for the first time I used to say that Wartile connects you with your playful inner self.

How does Unreal Engine help in developing a game like Wartile? Are there any unexpected benefits or challenges?

R. J.: The Unreal Engine has a good and strong visual engine that makes it possible for us, with little effort, to render our believable miniature landscapes. The workflow using Unreal is for us very straight forward and during the last two years the documentation and amount of tutorials is well supported.

Blueprints, which allows for a deep level of visual scripting, is also a major reason we chose Unreal. As a game designer and artist, Blueprints allows me to create the code needed to setup most level design and game features without being able to write a single line of code. We do, however, have a programmer, but still 85% of all code is done with Blueprints. This also allows me or other developers on the team to access, read and understand the back-end system of our game mechanics and, in some cases, tweak it by themselves.

Epic in general have also been very supportive towards small studios like ours. We were invited to join the Unreal Engine zone at the Nordic Game Connection in 2016, giving us a strong exposure in Northern Europe. This year we will attend EGX Rezzed in London, again in the Unreal Engine Zone.

Has the Dev Grant allowed you to do anything you otherwise would not have been able to?

R. J.: The Unreal Dev Grant came at the best possible time. We had cancelled our Kickstarter campaign and were running into a financial low point. The Unreal Dev Grant was an awesome boost of confidence. The recognition gave us a much-needed boost to keep going, to believe that we were making something special and people around us shared that opinion. I think the Dev Grant is great way to motivate and help out small studios showing great potential, and it enables the studio to get noticed and maybe attend a few exhibitions, increasing their visibility.

Do you have a release date or any milestones you’d like to share with our readers?

R. J.: It’s too early the reveal our exact release date, but we aim to launch on Early Access in Q1 this year. From there, on our goal is to release a major update every three week with new figurines, features and battle boards.

We have been running a closed alpha on Steam for some time with around 1,000 players who have played the game and provided us with feedback on the good and the bad. We have been listening and reaction accordingly. Today we feel that Wartile is ready to stand on its own as an Early Access title and we are looking forward to a close relationship with the community in developing this game to its full potential.