Fervescence: An Interview with Livia Llewellyn

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly Issue Seventy-Six. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly Issue Seventy-Six. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

———

The names of Livia Llewellyn’s stories hang in the air like magic words, shimmering, traced in flame: “Omphalos,” “Cinereous,” “Allochthon,” “Stabilimentum.” They form a kind of incantation, priming your mind for what will follow without the need for anything so mundane as a dictionary.

“Titles are gates,” she says, “and they should always open.”

* * *

Llewellyn was born in Anchorage, Alaska, and raised in Tacoma, Washington, growing up in what she describes as a quiet and conventional life in a white, middle-class suburb. “It was like I lived on one of those streets in a Twilight Zone episode,” she says, “Where time is stuck in a pristine, imaginary decade, and real life is happening somewhere beyond a border you can’t seem to find or pass.”

Real life did creep in slowly, through books, television and music. Llewellyn had a preoccupation with mystery, devouring the Three Investigators books and obsessing over Kolchak: The Night Stalker. “I spent the summer after the series aired prowling my neighborhood in a fake seersucker suit, tennis shoes, my grandfather’s fedora and carrying a little ‘investigative reporter’ kit that I made up myself, consisting of a pad of paper and a pen, a camera and a small homemade INS employee ID complete with a grainy black and white picture of Darren McGavin pasted onto it that I’d cut out of a TV Guide,” she says. “That was a great summer…I solved zero mysteries and got beat up by a bunch of the meaner kids because I looked like a total weirdo, but it was worth it.”

[pullquote]My life story is best served by my writing about it, not by talking about it.[/pullquote]

For all the joys – reading and listening to music and daydreaming – her childhood was not absent the existential horrors of the ‘burbs and the terrors of school. This was the Pacific Northwest living under the shadow of Ted Bundy and the Green River killer, after all. Llewellyn hints darkly at psychotic neighbors and strange men lurking in the woods. Years later, she would find in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet a kind of mirror to her youth. She avoids details, though. “My life story,” she says, “is best served by my writing about it, not by talking about it.”

Llewellyn’s specialty is erotic horror, which may seem a curious combination. Most consider horror to be transgressive, an examination of humanity’s darker impulses, while erotica is closely associated with pleasure; the two appear set in opposition, the death drives of Thanatos in constant struggle with the life-affirming Eros. Not so for Llewellyn. “Horror and erotica occupy the same dark edges of human existence,” she says. “We shove them both to the sides of daily routine, we confine them to moments of darkness or weakness or both. We tell ourselves that they’re wrong, they’re evil and against the rules of whatever god we worship, they’re unnatural, they should not ever be a part of the “normal” human experience. And yet we oscillate within horrific and erotic states of being for so much of our lives that they define us as much as, if not more than, any other states of being, even through their suppression or absence. I combine them because they’re already combined. Like love and hate or life and death, they’re not opposites but the same side of the coin, the opposite side being the unknowable void. As far as I’m concerned, they’re already combined. I just happen to point that out in my fiction.”

Erotica came first. “In seventh grade, I wrote a somewhat epic dirty ‘novel’ (i.e., about half a lined notebook) and passed it around to all my friends, who were properly thrilled and horrified,” she says. “I would give anything to read it again, but I have no idea what happened to it. I probably threw it away before my parents found it. I don’t remember why I wrote it – maybe I read some sex scenes in a Harold Robbins or Jackie Collins novel and thought, I can do better than that. I do recall getting a hold of a couple of Penthouses (everyone’s father had a couple of copies of Penthouse, Oui or Playboy stashed somewhere) and reading the fake “I can’t believe it happened to me” letters. Maybe they inspired me? Who knows?”

Erotica came first. “In seventh grade, I wrote a somewhat epic dirty ‘novel’ (i.e., about half a lined notebook) and passed it around to all my friends, who were properly thrilled and horrified,” she says. “I would give anything to read it again, but I have no idea what happened to it. I probably threw it away before my parents found it. I don’t remember why I wrote it – maybe I read some sex scenes in a Harold Robbins or Jackie Collins novel and thought, I can do better than that. I do recall getting a hold of a couple of Penthouses (everyone’s father had a couple of copies of Penthouse, Oui or Playboy stashed somewhere) and reading the fake “I can’t believe it happened to me” letters. Maybe they inspired me? Who knows?”

Horror followed along soon enough. “I took a creative fiction class in high school and wrote about a girl who turned into a giant spider and killed her parents and then everyone in her neighborhood,” she says. “Projection much? I’d be arrested and/or expelled for something like that nowadays, I’m sure, with years of court-ordered therapy or some such crap. We had to read our stories in class, and the teacher told me that I ruined mine because I was ‘too dramatic’ in my interpretation.”

While Llewellyn never stopped writing (mostly non-fiction and prose poetry in the style of the French Decadents), the focus of much of her life was the stage. Writing professionally only came when, tired of the drama and squabbling that often came with group creativity, she stopped acting. In 2005, her preoccupation with the erotic and the horrific coalesced into “Brimstone Orange.” Narcotic language; decaying relationships among family; transgressive sexuality encouraged by an outré force; these threads wind their way through much of Llewellyn’s work for the next decade. “That 500-word story just clicked on a switch,” she says, “and after years of trying all kinds of different artistic switches in my brain, it was the exact right switch, the one that made me realize I’d finally found the thing I would succeed at.”

[pullquote]People who love to read erotica don’t get tired of reading about fucking[/pullquote]

Presenting sex, particularly in the context of erotic horror, is a constant challenge. It is, at its core, a basic and repetitive act that, paradoxically, most people find infinitely compelling, like sunsets and watching waves roll in at the sea shore. “It’s typically the familiarity of the sexual act that excites readers more than the events and details surrounding it,” says Llewellyn. “It’s not a challenge to write those acts because people who love to read erotica don’t get tired of reading about fucking, and will happily read stories about the same types of fucking over and over again.”

Many writers of regular erotica are happy to oblige their audiences, writing the same story over and over again. In fact, there isn’t a genre that doesn’t share this characteristic. We tend to seek out the same experiences in stories time after time, to revel in the variations, like Bach’s fugues, like sex itself.

“I’m happier putting my protagonists in very strange and unsexy situations, and then seeing if I can write my way to the same couple of positions I always write about, even if the position is with something utterly inhuman in nature,” explains Llewellyn. “Where I lose readers is in the uncertainty of what’s going to happen – most people read erotica for a certain degree of sexual and emotional comfort, not because they’re looking forward to renegotiating that comfort zone when some level of pain, supernatural violence or psychological distress becomes (for better or worse) a part of the sexual act. Some readers may be into that, but most just want a very straightforward story (powerful billionaire and naïve young protégé!) with a very ordinary sexual act and a very ordinary ending – no surprises at all.”

Another challenge is that sex is silent. “We as humans tend to stop the narrative between each other when we start having sex,” says Llewellyn. “That’s why one partner may think they’re achieving heights of togetherness that they never dreamed possible with another person while the other partner may feel disgust or boredom or violation. We’ve taught ourselves to shut down verbal communication completely when the fucking commences – and that tends to hold true in a lot of fiction and visual media. People start kissing, and there’s no more dialog – so how can we as audience members really know what’s going on between the two characters anymore?

[pullquote]People start kissing, and there’s no more dialog – so how can we as audience members really know what’s going on between the two characters anymore?[/pullquote]

“All I try to do is to makes sure that the dialog continues during the physical interactions, even if it’s so uncomfortable and nakedly honest that it repels the reader. I think entwining erotica with horror and fantastical situations help, because the conventions of genre fiction dictate that you can’t suddenly stop pretending that environment doesn’t exist, that it’s actually permissible for you to continue inserting the world you’ve created and the creatures and rules you’ve created into every moment of your protagonists’ lives, even the most intimate ones.”

* * *

“We live in a new golden age of horror,” says Llewellyn. “I’m thrilled to see so many high-quality films, TV shows, and novels being created, but I’m perfectly fine with them existing on the sidelines of popular culture, and I’m fine with my fiction existing at the sidelines with them. And if I’m ridiculed or ostracized for writing horror, and if there are less opportunities for publication than other genres, I’m also fine with that. Like the Greek oracles, there are certain aspects of our function as writers of horror that by necessity set us apart from the rest of society. Artists exist in a duality of ‘above’ and ‘below’ everyone else, and I think it’s where we both want and need to be.”

Among her influences are Baudelaire, Verlaine, Rimbaud, Bataille, Huysmans, Nin – writers all known for working in heightened and drug-induced states. And isn’t sexual arousal a perception-altering state? “It never occurred to me that this was something that was different or set apart from other forms of writing,” she says. “I think also because I was a teenager when I started reading all these authors, I didn’t think of them as doing something out of the ordinary. When you’re young, you’re basically living at such a freakishly emotional and physically heightened state, it’s like you’re Krakatoa inside. These writers spoke and thought the way I did, so when I write like that now, it’s because my protagonists are women who see the world in this way, who are young and in the throes of growing up, or are older but haven’t needed to or been able to escape that heightened state of being.”

There is something peculiar about Llewellyn’s stories. Often, they feel like parables, hinting at some hidden truth, like the tome of forbidden knowledge that you know you shouldn’t open, but also cannot resist. In other ways, they are like dreams – vivid and immediate during the reading yet rendered ambiguous in waking light. Yet they hang on you, heavy phantoms, leaving you unsure you’ve actually woken up. Her prose is hypnotic, lulling you, leading you on, oblivious to the fact that you will find words within that scorch and singe. You can’t read one of her stories and come away without scars.

This is intentional, a kind of ritual taking place between writer and reader. Llewellyn pours through encyclopedias, dictionaries and thesauri to collect the strange words that act as titles or chapter names of her stories. Very often, the titles come first, the stories unfolding themselves around the sound and contour and meaning of the word. “And they may be abstract or incomprehensible in design, but they each convey a specific mood or trigger a response that acts as a mini-representation of the story as well as an invitation,” she says. “In a way, they are a magickal invocation of a kind. You see the shape of the story at the top of the page, you might not be able to pronounce it, but when you sound the word out silently in your mind, and it triggers something inside, it awakens the notion of strangeness and otherness and opens you up to accepting an experience you might not have otherwise been as open to experiencing.”

This is intentional, a kind of ritual taking place between writer and reader. Llewellyn pours through encyclopedias, dictionaries and thesauri to collect the strange words that act as titles or chapter names of her stories. Very often, the titles come first, the stories unfolding themselves around the sound and contour and meaning of the word. “And they may be abstract or incomprehensible in design, but they each convey a specific mood or trigger a response that acts as a mini-representation of the story as well as an invitation,” she says. “In a way, they are a magickal invocation of a kind. You see the shape of the story at the top of the page, you might not be able to pronounce it, but when you sound the word out silently in your mind, and it triggers something inside, it awakens the notion of strangeness and otherness and opens you up to accepting an experience you might not have otherwise been as open to experiencing.”

This is the core of Llewellyn’s work. All these ideas – of altered states of mind, of sex existing somewhere outside of narrative, of horror lurking at the edges of acceptability, of magick, of secrets – speak of being removed from mundane reality. Llewellyn’s stories invite the reader to cross the threshold, to find a kind of transfiguration, like the ones that find so many her protagonists initiated into something outside of consensus reality.

“Sex is the alchemical cauldron,” says Llewellyn, “like the monsters and the magic and whatever parts of the universe are coming together or apart, it’s part of what transforms my protagonist into whatever it is she needs to be or is fated to be.”

———

Author’s Note

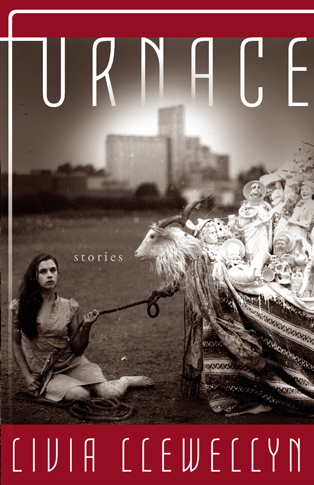

Livia Llewellyn’s first collection, Engines of Desire, is about to be joined by her long awaited second collection, Furnace, from Word Horde. You can also support her work on Patreon and receive access to her Black Century series.

The photograph, “Journey to the Tower,” by Mike Garlington, graces the cover of Furnace. You can see more of his work on his website.

* * *

This is the fifth installment in an occasional series that examines the creators behind the new strain of literary horror. This was spurred on by my recent discovery of this rich new vein of writing and my dismay that no one I talk to seems to know much about it. Every book store I visit, I check for work by the likes of Simon Strantzas, Scott Nicolay, Kaaron Warren and more. Almost every time, I leave disappointed. This is my small attempt at spreading the word.

The first interview was with Laird Barron, in Unwinnable Weekly Issue One. The second interview was with John Langan, in Unwinnable Weekly Issue Forty-Three. The third interview was with Stephen Graham Jones, in Unwinnable Weekly Issue Fifty-Eight. The fourth interview was with Paul Tremblay in Unwinnable Weekly Issue Sixty-Seven.

At Livia Llewellyn’s suggestion, Nathan Ballingrud (North American Lake Monsters, The Visible Filth) will be the next victim…

———

Stu Horvath is the editor in chief of Unwinnable. He reads a lot, drinks whiskey and spends his free time calling up demons. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.