Apotheon/Apollyon

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

Apotheon begins with war and punishment. Zeus, king of all gods, has grown resentful of humanity and in his ire has revoked the gifts of the divine. Apollo removes the sun from the sky, Demeter withers the crops and Poseidon wracks the world with earthquakes and floods. The earth is set adrift in darkness.

It falls to the warrior Nikandreos to set things right. Goaded by Hera, Zeus’ vengeful wife, he climbs Mount Olympus to lay siege to the gods and bring their powers back to earth. In claiming the portfolio of a god, Nikandreos becomes something more than human, an apotheon.

Apotheosis was a common theme in Hellenistic culture. City-states venerated long dead heroes like Heracles, Theseus and Orestes as deities, their characteristics blending with the identities of their people. Great artists like Homer were similarly revered. Sometimes, even the living were declared divine – Philip II of Macedonia, Alexander the Great’s father, was exalted along with the Olympian gods during his lifetime.

Nikandreos’ struggle to restore order to the world through supernatural means seems to be a parable for humankind’s struggle against the depredations of the natural world. Only in harnessing the environment around us did we take our first steps towards a meaningful civilization. Freed from superstition, our species experienced a different kind of apotheosis, less concerned with divinity than it was the ability to control our own destiny.

And yet, whenever letters of Apotheon’s title screen appeared, I could only think of another Greek word: apollyon, a verb meaning “to destroy.”

After all, Nikandreos’ transition is one of blood, steel and fire. A warrior through and through, he assumes his new powers by slaying or otherwise subduing the gods of old. He doesn’t climb Olympus to seize a throne for himself. He is there to raze it all to the ground and to sew salt in the ruins.

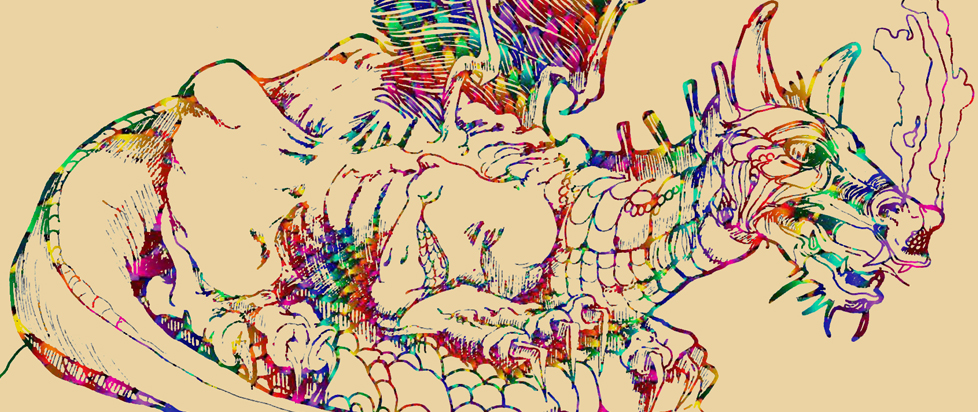

It is grim work for a game so beautiful to behold. Apotheon’s art style mimics the decorations of amphoras and urns more than 2,000 years ago, elegant black figures dancing across a rich orange world. I’ve seen examples of these vases in museums, vivid despite the millennia, gorgeous but so terribly fragile. Many have been shattered and pieced back together again. It astounds me that those shards survived to the modern day.

Many did not. Exekias, a potter who lived from 545 to 520 BC, is considered the true master of black-figure style pottery and yet only twelve of his vessels are known to exist and only two of them bear his painting. Similarly, Pliny the Elder considered Apollodorus to be the greatest painter of his age and the legacy of his techniques echo all the way to the Renaissance. Yet all of his paintings are lost.

I wonder how much we can trust our notions of aesthetics. We call the Venus de Milo a masterpiece, but is it really? Does she beguile us because she is beautiful, or because her missing arms are so mysterious? Do we feel her influence in art because of some kind of genuine artistic merit, or is it merely down to the happy accident of her survival? She did not withstand the test of time in the same way that Shakespeare did, worming his way into the fabric of culture through constant performance and scrutiny. She hid, for long centuries, buried in a cave.

Apollyon.

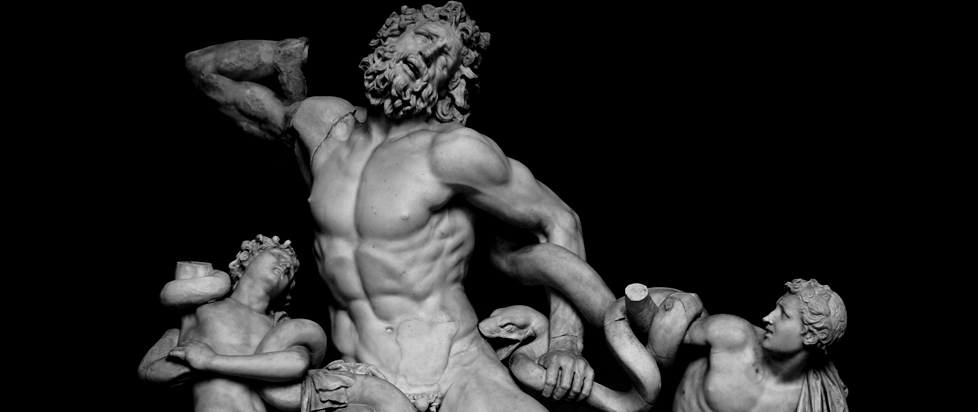

Time is the great destroyer. It devours everything, inexorably. Paintings burn, pottery shatters, statues erode, edifices crumble. And humankind is its agent. Who else can take a hammer to an ancient temple or bomb a church or devise a furnace hot enough to melt bronze? What madman buried The Laocoön, leaving it to crack and cleave in the straining earth?

The divine heroes lie buried, too. Though adored, worship of the apotheons took place at their heroon, a kind of mausoleum shrine. They did not ascend to Olympus to enjoy some kind of eternal reward. These chthonic gods stay with their bones, subterranean, infusing the soil with their glory.

At the end of Apotheon, when Nikandreos stands triumphant, he is too late. The ceaseless storms and terrible cataclysms have left humanity extinct. Zeus, though vanquished, has achieved his apollyon.

Nikandreos kneels and sinks his hands into the earth, forming it into the shape of a human figure. Using his stolen lightning, he quickens the sculpture, a lone act of creation amidst the desolation. They stare at each other in silence for a long moment before the screen goes dark.

Without all the strife and cruelty, that new man would not exist. Nikandreos can only create because he has destroyed. Without his battles he would not have the means, the powers of the gods to harness in such a way, but also, he would not have the need or desire. Wreckage is a teacher.

And I look back on our long history of art and creation, and all the sublime beauty we have left to decay, and all the crumbling artifacts that remain and wonder if ruin and beauty are the same thing.