Rookie of the Year: The Shining and Alex Colville

Editor’s Note: This story has been reprinted from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Seventeen. Want to check it out in all its wonderfully-laid-out glory? Pick up this issue or subscribe today!

———

Fuck you, Stanley Kubrick. You’ve turned me into a nut, straight out of Room 237 – an insane documentary that’s not to be missed if you enjoy wacky fans espousing off-the-wall but often intriguing theories about The Shining.

What started as something I thought of as a fun exercise has become an obsession.

I’ve begun seeing things in The Shining that may or may not be intentional. And more and more, I’m becoming convinced that they are.

It all started in Toronto. A few weeks ago, I stumbled upon an Alex Colville exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario. The show blew my mind. Few things get me quite as jazzed as discovering a new artist, at least one that’s new to me. Speaking simplistically, Colville reminded me of a Canadian Edward Hopper. Of course that doesn’t come close to telling the full story. Works like “Horse and Train,” “Traveller” and “Kiss With Honda” – my favorite pieces in the show – have a powerful sense of foreboding and use light to create moods that build on Hopper more than simply emulate him.

Inside the gallery, I moved from painting to painting like I’d never seen art before. Little did I know, I had already been introduced to Colville’s work, if only subconsciously.

Indeed, the main reason I find my Colville discovery worth sharing – and why I became obsessed with The Shining – is because of a sign that hung in the exhibition, one which my dad fortuitously photographed, allowing me to transcribe it here:

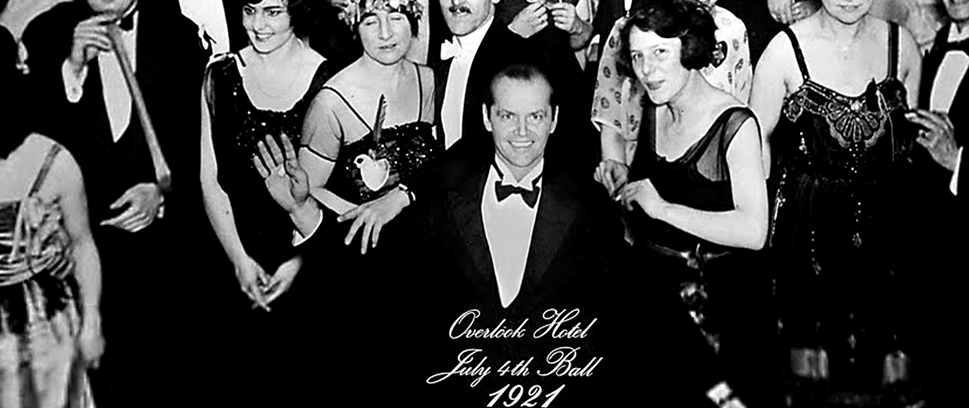

IN STANLEY KUBRICK’S

THE SHINING (1980)

Like Alex Colville, British filmmaker Stanley Kubrick was a meticulous planner, carefully arranging the contents of each shot. His famous horror film is permeated by Canadian art, including reproductions of the four Colville paintings you see in this corner. But the filmmaker famously remained tight-lipped about his motivations. Was he drawn to Colville’s animal imagery? The multi-layered quality of the works? Colville’s interest in the darker side of human nature? We can only speculate.

I decided to speculate.

Not long after seeing the exhibition, I re-watched The Shining – possibly the most overly analyzed film in movie history – to get the context for the use of Colville’s works by Kubrick.

Did Colville’s paintings shed any light on The Shining? Or vice versa? I figured it was worth checking out, if only for the thrill of seeing one of the greatest movies of all time from a new vantage point.

Now, I can’t ever turn back.

* * *

Painting: “Woman and Terrier”

Time in film (according to the AGO sign): 0:10:57

Jack Torrance has just been told about Delbert Grady, the former Overlook Hotel caretaker who hacked and stacked his wife and two daughters and then “put both barrels of a shotgun in his mouth.” Back home in Boulder, his son Danny’s imaginary friend Tony has told him his father has now gotten the job and is about to call with the news. Sure enough, the phone rings and Jack’s wife Wendy answers.

Jack Torrance has just been told about Delbert Grady, the former Overlook Hotel caretaker who hacked and stacked his wife and two daughters and then “put both barrels of a shotgun in his mouth.” Back home in Boulder, his son Danny’s imaginary friend Tony has told him his father has now gotten the job and is about to call with the news. Sure enough, the phone rings and Jack’s wife Wendy answers.

As Shelley Duvall sits down to speak to Jack Nicholson, Colville’s “Woman and Terrier” is clearly visible along the back wall, above a black and white television set. The painting is of a woman hugging a terrier, her face mostly obscured by the dog’s head, but with the corner of her left eye just visible, peering out. In a recent interview with the Andrew Hunter, who curated the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Colville show, Brian Bethune writes:

There’s “Woman with Terrier” [sic], one of The Shining four, which Colville once jokingly described as “my Madonna and Child; of course in my world the child is a dog.” Colville had “a peculiar idea of dogs,” Hunter adds. “They are sentient but incapable of evil – they can see. People and dogs in his art represent distracted and hyperaware capacity for evil and innocence. The woman’s face, unsurprisingly, is hidden by the terrier. “Colville’s averted faces implicate viewers in his works, make us feel like voyeurs. When someone in a Colville looks directly at the viewer,” Hunter continues, “it’s as though you have interrupted him or her, broken in on a private scene.”

[“Unpacking the real Alex Colville,” Maclean’s, Aug. 22. 2014]

We’ve just had a less-than-subtle bit of foreshadowing as to where this film is going. And there is “Woman and Terrier” along the back wall. The child and the dog of “Madonna and Child” may be switched by Colville, but they’ve been switched back by Kubrick; Danny can sense evil, and he knows it’s coming. At the same time, his mother has seen the signs – and is about to see a whole lot more of them – but is blissfully unaware of the gravity, even as she later embraces her child, screaming, “Wake up, Danny! Wake up!”

We’ve just had a less-than-subtle bit of foreshadowing as to where this film is going. And there is “Woman and Terrier” along the back wall. The child and the dog of “Madonna and Child” may be switched by Colville, but they’ve been switched back by Kubrick; Danny can sense evil, and he knows it’s coming. At the same time, his mother has seen the signs – and is about to see a whole lot more of them – but is blissfully unaware of the gravity, even as she later embraces her child, screaming, “Wake up, Danny! Wake up!”

Now we’re inside Wendy’s home, and we’re watching her take a private phone call, and a Colville character is peeking at us from the far wall, reminding us we’re simply voyeurs to the great horror that approaches.

Kubrick has set the scene for what a Colville painting means in The Shining.

And then the blood comes pouring out of the elevators.

Painting: “Horse and Train”

Time in film: 0:14:31

The Torrances seem to have excellent taste in art – though perhaps it’s a bit out of the ordinary.

The Torrances seem to have excellent taste in art – though perhaps it’s a bit out of the ordinary.

In a 1957 letter to T.R. MacDonald, the director and curator of the Art Gallery of Hamilton, Alex Colville wrote that he was “delighted” that his 1954 painting “Horse and Train” had been bought by the gallery.

“I have always thought it was quite good,” Colville wrote, in his handsome, cursive script, “but realized that few individuals would buy it for hanging in a house (most people seem to consider it exceedingly morbid) … ”

[The Toronto Star, July 26, 2013]

Danny has just had his vision of the two girls and the cascading blood, and has woken in his bedroom after passing out in front of the bathroom mirror. A pediatrician has been brought in to treat him. After an examination, the doctor and Wendy walk to the living room, where they discuss Jack’s issues with alcohol, how Jack once dislocated Danny’s arm, and how that seemingly precipitated the first appearance of the mysterious Tony – who lives in Danny’s teeth, Danny says, but hides in his stomach.

As they pass through the hallway, there it is on the wall: “Horse and Train” – among Colville’s most recognizable works (I’ve been using it as desktop wallpaper since I returned from Toronto). It’s gray and cloudy; a black horse is galloping down the tracks toward an oncoming train. It’s a gripping painting, inspired by a couplet from an old poem on the futility of maintaining convention in the face of oncoming, violent change. Maybe the horse will veer off the tracks, or maybe the train will find a way to brake in time. The possibility is real, though it doesn’t seem likely.

As they pass through the hallway, there it is on the wall: “Horse and Train” – among Colville’s most recognizable works (I’ve been using it as desktop wallpaper since I returned from Toronto). It’s gray and cloudy; a black horse is galloping down the tracks toward an oncoming train. It’s a gripping painting, inspired by a couplet from an old poem on the futility of maintaining convention in the face of oncoming, violent change. Maybe the horse will veer off the tracks, or maybe the train will find a way to brake in time. The possibility is real, though it doesn’t seem likely.

The conversation between Wendy and the pediatrician makes it clear Jack has issues – issues that are going to surface, in a big way, during five months of seclusion. The horse and train are gathering speed, on what appears to be a collision course.

As if the stubborn horse is allowed to speak through Kubrick’s dialogue, the first words spoken after the painting moves across the screen, from left to right, and then disappears, come from the doctor:

“Mrs. Torrance, I don’t think you have anything to worry about.”

Yeah, right.

In the very next scene, Jack, Wendy and Danny are filmed from above, speeding along a mountain road. When they arrive at their destination, the car and the road fade, and the Overlook Hotel slowly materializes over them on screen, an immovable object at the end of their road, the armored train to their galloping horse.

Painting: “Dog, Boy, and St. John River” (mistakenly transposed with “Moon and Cow” at the AGO exhibition)

Time in film: 0:58:30

In case you think this is all just a happy coincidence, that a rogue set designer tossed a couple Colvilles in the Torrance’s apartment as an art-school in-joke, try this next one on for size:

In case you think this is all just a happy coincidence, that a rogue set designer tossed a couple Colvilles in the Torrance’s apartment as an art-school in-joke, try this next one on for size:

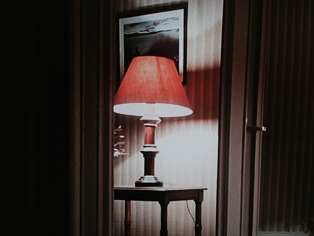

As Danny comes around the corner and peers through the door of Room 237 – the first time any of the room’s interior is revealed – the first thing you see inside it is a lighted table lamp and “Dog, Boy, and St. John River.”

This was my first goosebumps moment. In truth, I was expecting to see “Moon and Cow” here, as this is the time in the film the AGO mistakenly marks its appearance, and because Danny is wearing his conspiracy-charged Apollo 11 sweater (if Kubrick had faked the moon landing, Colville’s “Moon and Cow” would have been the final proof, right?). But the placement of “Dog, Boy, and St. John River” could hardly be more perfect. The painting, another of Colville’s most iconic pieces, depicts a boy, holding a shotgun, looking out over a river with a dog trailing just behind him.

Again, we can’t see the human face. We’re looking at the boy from behind. Nor can we see Danny’s face as he peers through the door – we’re seeing Room 237 from his point of view, almost in the same way we’re seeing St. John River from the boy’s.

Another Colville dog makes its appearance (although he’s obscured by the lamp in the film), and again there is that hint of extrasensory perception. What are the dog and its owner looking at, or for? It could be an innocent hunting trip, but the light and perspective makes it seem there’s something sinister out there, over the large expanse of water in the distance. Or is it just us, creeping up on the boy and the dog through the reeds?

As I paused the film here to take a couple screen shots, two more details jumped out at me, and I nearly had to stop and catch my breath:

1. If Colville believed a dog can sense evil, then perhaps he’s hiding behind the boy at the same time he is following him. The boy is armed with a weapon and, however fearful, is facing whatever is to come next; the dog joins him, but at a distance. Is that the relationship between Danny and Tony – or Danny and his ability to “shine” – as they creep toward the source of the Overlook Hotel’s hidden terror? Is it a coincidence that the boy and dog are at the mouth of a body of water, and Danny and Tony (and later Jack) are about to be attacked by a naked witch soaking in a bathtub? Or that Kubrick is again reminding movie watchers that they’re indulging in voyeurism as something wicked this way comes?

2. At first I almost thought it was a different Colville work – the boy is on the wrong side of the frame – until I realized the painting is reversed; it’s actually being reflected in a mirror. Kubrick loves to play with mirrors in The Shining – and to fuck with us in the process, refracting Jack several times in mirrors throughout the movie, sometimes showing both Jack in the flesh and his mirrored version in the same shot.

It cannot be an accident – it is most certainly a conscious choice by Kubrick – that the first thing you see in Room 237, even before you see the key in the door, is the painting of a boy holding a weapon, in mirror image; is it not, later in the film, a boy, holding a knife, who scrawls an oft-spoken word in red lipstick onto a door – a word that’s true meaning isn’t revealed until it is viewed through a mirror?

Painting: “Moon and Cow” (mistakenly transposed with “Dog, Boy, and St. John River” at the AGO exhibition)

Time in film: 2:09:32

And now we’re down to the final stretch, a mad dash for survival at the Overlook Hotel.

Jack has slashed through the bathroom door and delivered his “Here’s Johnny!” line and is now in hot pursuit of Danny after axing Dick Halloran.

Wendy, who narrowly escaped the bathroom attack, is rushing upstairs holding the knife she used to slash Jack’s hand. As she makes her way up, she passes several paintings, none more noticeable than Colville’s “Moon and Cow,” which remains in frame for a few short moments; first it’s on her left, then it passes to her right.

And the painting itself? It’s a fucking cow, lying in a pasture, on the right of the frame, looking up at the moon, to his left. It’s a pastoral piece and, though a well-known one, not as gripping, in my opinion, as some of Colville’s other classics.

Damn you, Kubrick. You had me with “Dog, Boy, and St. John River,” but I couldn’t for the life of me understand your specific Colville choice as it pertains to this scene. Yes, the animal imagery in all the artwork is huge throughout the film, and especially fits here, as Wendy, when she gets to the next flight, sees a man in a dog/bear/pig (take your pick) costume performing fellatio on a tuxedoed party guest/ghost.

But other than that, I was stumped. I left the movie paused on a knife-wielding Wendy, mid-ascent. How is it that the first three paintings, when placed in context, could tell the story of The Shining – from foreshadowing to extrasensory perception to voyeurism and even to specific plot parallels – while the last one dropped the ball so mysteriously? I felt lost.

Still, since I couldn’t help but seeing this project to its conclusion – that is, of me potentially losing my mind – I kept watching, and looking. Looking way too hard. Or just hard enough?

And then there was this:

And then there was this:

In the climactic scene, mere minutes later, when Jack falls to the snowy ground in the hedge maze, the final shot you see of him – before his frozen body appears the next morning – is Jack slumped over on the ground. Jack has fallen to the left of the frame, and there’s a bright light in the distance to his right.

Just like “Moon and Cow” – you know, if you were to view the painting through a mirror.

* * *

As for the director and the artist: Stanley Kubrick died in 1999 and Alex Colville died last year.

But as I discovered in Toronto, and then later again in my living room in front of my TV, their work lives and breathes. If you let yourself, you can spend an entire day reading about it, pausing it, rewinding it, screen grabbing it and ultimately seeing whatever you’d like to in it.

Where Kubrick and Colville meet, there is most certainly a spark. Kubrick definitely placed those Colville paintings where they are for a reason. What makes it fascinating is how it seems to make perfect sense, yet remains elusive. The paintings don’t morph into written signs when you pause at the right frame. They remain the same as the paintings I saw on the wall in Toronto, packed with meaning and associations for each person who views them. Kubrick saw them, too, and cooked them into The Shining. All we can do is smell and taste and isolate the ingredients to try to figure out the recipe – even if it takes forever.

There is line toward the end of Room 237 that seems fitting: “There must be a lot of stuff in there that nobody has yet seen. And so people ought to keep watching.”

I went down that rabbit hole. I’m looking forward to reading about the next nut who does, too.

———

Follow Matt Marrone on Twitter @TheBigM.