Godzilla: Savior?

“Why are so many students missing?”

It’s the first question that pops into my mind as the bell rings to start class. I had been teaching in Busan, South Korea for about half a year at this point – March 2011 – and if there’s one thing I’d learned in that time it was that kids don’t skip school. This day was different, though, with numerous students absent in each class that came in through the doors. Light rain was steadily coming down outside, but it was nothing worth worrying about.

[pullquote]Godzilla is all about perspective, and from its perspective humans have a role to play only until they are utterly humbled by forces beyond their control.[/pullquote]

At least, that’s what I thought.

“Radiation,” my coworker says.

Oh yeah, that. Only a week or so had passed since the Tohoku earthquake struck Japan, triggering devastating tsunami waves and bringing the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant to its knees, but the fear over “secondhand” contamination was already palpable in Korea.

Not that they shouldn’t have been worried. Residents in Busan, nestled between mountains and the beaches of Korea’s southeast coast, were already closer to some Japanese cities than they were to Seoul. The trajectory of the wind currents, and weather patterns in general, suddenly became of the upmost importance. Radiation detectors were swiftly brought into airports, screening anyone flying in from Japan, staying in place even months after the disaster. When the possibility was broached that radiation might drop in the form of contaminated rain, well, it was alarming enough that scores of children were simply kept from attending school.

Even some teachers had trouble keeping themselves in check. I’ll never forget the worried look on one coworker’s face when she tried to avoid a puddle of water only to slip and fall right into another.

In an effort to combat the potential effects of radiation, meanwhile, schools began stocking up on seaweed and supplying it during daily lunch breaks, hoping the food’s natural iodine content would prevent airborne thyroid poisoning.

In some of my classes, English took a backseat to watching videos of the tsunami flooding city streets, uprooting houses and carrying away rooftops, and seeing frightened drivers desperately try to outpace the encroaching waves. There was some fear of aftershocks hitting Korea as well, with tsunami warnings coming and, fortunately, going uneventfully.

In some of my classes, English took a backseat to watching videos of the tsunami flooding city streets, uprooting houses and carrying away rooftops, and seeing frightened drivers desperately try to outpace the encroaching waves. There was some fear of aftershocks hitting Korea as well, with tsunami warnings coming and, fortunately, going uneventfully.

It was a time that I thought had been left in the past, until I saw the new Godzilla flick. I knew the film would traffic in current events, nuclear power and radiation – that is what Godzilla does, obviously – but I found myself feeling unexpectedly defenseless as I watched students and teachers evacuate a school while a power plant collapsed in the background. When the radiation-consuming MUTO escaped Japan and fled to Hawaii with Godzilla trailing behind, causing tsunamis, drowning people and wreaking havoc of his own, I nearly closed my eyes to avoid the chaos.

It was strange. For a movie involving giant fighting monsters, it felt surprisingly real and relevant. Those scenes stuck with me far past the ending, making as big an impression as the epic battles themselves.

And this is coming from someone who didn’t truly experience much of anything – especially compared to those who’ve actually been caught in natural and man-made disasters. I can only imagine how someone who lived relatively close to Fukushima or had to hurriedly evacuate a hurricane zone would react to the scenes onscreen.

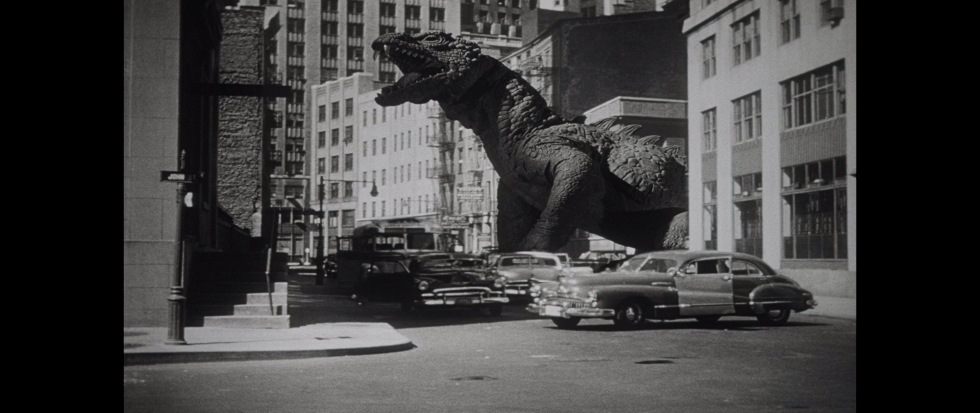

Of course, the very first Godzilla did something similar. Haunting even today, Ishiro Honda’s 1954 original employed imagery that would’ve been ghastly for anyone living in Japan post-World War II: irradiated children, cities burning to the ground, overflowing hospitals. It was as big a “HERE BE DRAGONS” warning as there could’ve been, and subtle it was not. Honda described his film simply, saying, “Mankind had created the Bomb, and now nature was going to take revenge on mankind.”

Whereas the 1954 Godzilla was a warning against treading down the path illuminated by the atom bomb, the latest variation of the creature has been updated for a world that’s already decided to take what was marked as the wrong fork in the road. Nuclear power is a constant fact of life, and now Godzilla is back to reveal how nature will react to our lust for energy. The answer is pretty clear: more disasters that become harder to contain, and nightmares we couldn’t begin to imagine.

Numerous times, Godzilla is described as an act of nature restoring balance to the world. It’s been argued that this new monster is too benevolent, that by having him essentially rise from the sea to take on the MUTOs – dangerous creatures that exist purely because of our never-ending pursuit of energy – humanity is let off the hook for its contributions to global warming and other disasters. After all, why bother changing anything if nature is simply going to self-correct and then leave us alone?

It’s not that simple, though. Even if nature does self-correct – whether or not it does, scientists at least believe it reacts to our behavior around the world – where does that leave us? Cities in Japan have been deserted; Hawaii has been toppled by tsunamis; Las Vegas gets destroyed and San Francisco becomes virtually unrecognizable. And that’s to say nothing of the body count, which is likely in the stratosphere.

Is Godzilla our “savior,” as movie-world CNN asks before the credits roll? Certainly, he killed off the MUTOs and allowed mankind to survive, but there’s a question mark there for a reason. This monster doesn’t care for humanity; he and the MUTOs are operating on a completely different level – Godzilla is all about perspective, and from its perspective humans have a role to play only until they are utterly humbled by forces beyond their control. Like David Ehrlich wrote on The Dissolve, at some point the story stops being about us even if we’re the storytellers.

Is Godzilla our “savior,” as movie-world CNN asks before the credits roll? Certainly, he killed off the MUTOs and allowed mankind to survive, but there’s a question mark there for a reason. This monster doesn’t care for humanity; he and the MUTOs are operating on a completely different level – Godzilla is all about perspective, and from its perspective humans have a role to play only until they are utterly humbled by forces beyond their control. Like David Ehrlich wrote on The Dissolve, at some point the story stops being about us even if we’re the storytellers.

Just as Godzilla evolved from destroyer into a more complicated beast over the course of numerous films – at times good and bad, a problem to be managed and survived rather than solved or even contained – the latest incarnation embodies multiple layers. Upon first seeing the film recreate horrible real-life disasters so precisely, I worried it’d traffic in powerful imagery without good cause. Luckily, it offers an allegory as worthwhile as the original. Without correcting our own destructive tendencies, we risk leaving our livelihood in the hands of much more reactionary and much less caring forces. By the end of Godzilla, humanity survived, but how many humans did not? And what kind of strange, deadly new world are those left behind inhabiting?