Worlds Without End

I don’t like endings. I’m the kind of person who stays in the theater until the end of the credits, who re-reads books over and over and over again, who roams pointlessly through the rescued kingdoms of my videogame worlds. To me, when the screen finally goes black, or the last sentence ends, or the dreaded “Game Over” looms before my eyes, it feels like rejection – like the director, author, developer had revoked my passport to this other world. The curtain, so briefly pulled away, had been closed again, and once Virgil said “the end,” I was no longer allowed inside.

Good thing no one does that anymore.

[pullquote]We look at stories as excerpts from a longer and wider fabric, as portals into a persistent, if fictional, world.[/pullquote]

Death isn’t what it used to be

Virtual pets don’t die anymore, laments Wired’s Nate Lanxon in his piece “My Horse is Immortal: Free-to-Play is Killing Death in Gaming.” Looking to the Tamagotchi, the pet simulator toy from the nineties, Lanxon argues that one of the explosively popular toy’s main appeals was the real possibility of death. “Kids became so emotionally invested in their pets they would habitually return to check on their well-being, to go truant in the name of animal safety,” he points out. “No doubt the ability of these digital animals to die from neglect or old age was fundamental to their success.”

Tamagotchi was paid for in advance. It didn’t matter if it died – Bandai had already cashed in, and kids could hatch a new pet anyway. The landscape, thanks to the internet, casual games, Facebook and iPhones has entirely changed this for new businesses. Moshi Monsters, although a free-to-play game, has a paid-for membership model for gamers who want a richer experience. My Horse, also free-to-play, sells perks using in-app purchases on the iPhone. Why would you let your customers kill the only reason they have to give you money?

For Lanxon, removing the threat of death cheapens the gaming experience (even, ironically, as it thickens the developers’ wallets). Is it the tie with reality – i.e. death – that makes our fantasy meaningful, at least with regard to our virtual pets?

Functional immortality in gaming at large is nothing new, of course. Otherwise, how many of us would still be playing…anything? Multiple lives, and the chance to try and try again, is the main mechanic of almost every videogame ever. It’s what makes videogames playable to those of us who aren’t secret agents, supersoldiers or magical beings. It’s also what makes an ‘actual’ death in a videogame so strangely affecting.

Functional immortality in gaming at large is nothing new, of course. Otherwise, how many of us would still be playing…anything? Multiple lives, and the chance to try and try again, is the main mechanic of almost every videogame ever. It’s what makes videogames playable to those of us who aren’t secret agents, supersoldiers or magical beings. It’s also what makes an ‘actual’ death in a videogame so strangely affecting.

In the turn-based strategy game Fire Emblem, characters who fall in battle suffer “permadeath,” a curious term that is nevertheless necessary in the world of videogames. When the characters, units in your army, fall in battle, players don’t fail the level; they merely lose that character for the rest of the game. No Phoenix Downs or good night’s sleep will revive them; they’ve ‘died’ in that playthrough continuity, and other characters may comment on or discuss their death throughout the rest of the story.

Even permadeath, though, can be undone by restarting the level. Not so Aerith’s death in Final Fantasy VII. The videogame world was rocked in 1997 when a member of the player party – who by all appearances still had skills to unlock and levels to grow just like the rest of the cast – was killed off in a cutscene, with no way to bring her back (if you play by the rules, that is). Players spent hours looking for the secret to reviving Aerith, rumored to be hidden in the game’s code, and failing that they hacked the game to reinsert her into the party. Turns out that if you do, long-buried dialogue code for Aerith is reactivated, in which she comments along with the rest of the party on events that occurred after her death. Apparently the decision to kill her off came later in development, and her posthumous dialogue was left buried in the game code.

“…And pray for a resurrection.”

For how many years now has Bruce Wayne, a.k.a. the Dark Knight, a.k.a. Batman, been a thirty-something crimefighter? First introduced in 1939, the character has been seen fighting Nazis in World War II, swinging through 1950s-style suburbia, wooing women with crazy 1960s hairdos, using computers that printed out data onto pieces of paper, and brooding on the coming of the new millenium. He’s even been killed a time or two, and yet there’s still always a Batman – and even a Bruce Wayne – running around the pages of our comic books.

For how many years now has Bruce Wayne, a.k.a. the Dark Knight, a.k.a. Batman, been a thirty-something crimefighter? First introduced in 1939, the character has been seen fighting Nazis in World War II, swinging through 1950s-style suburbia, wooing women with crazy 1960s hairdos, using computers that printed out data onto pieces of paper, and brooding on the coming of the new millenium. He’s even been killed a time or two, and yet there’s still always a Batman – and even a Bruce Wayne – running around the pages of our comic books.

Superheroes die and return all the time, so much so that even within the world death is no longer considered a permanent state. Alan Moore ripped on this trope in his Top 10, where a funeral for the superhero known as Girl One looks more like comedy and fourth-wall cracking than tragedy.

But even in the main comic book worlds, where writers depend on our love of their characters to ensure our continued support, the characters have acknowledged that death is not what it once was. At Martian Manhunter’s funeral in Final Crisis issue #2, Superman solemnly eulogizes: “We’ll all miss him. And pray for a resurrection.” Having experienced it firsthand, Superman knows that even death is not necessarily the end.

The world is not enough

It’s not just in the world of comics that we see characters wade untouched through the decades. Case in point: James Bond. But in this case, Bond’s literary immortality is not for a lack of effort on his creator’s part. Ian Fleming’s 1957 novel From Russia, with Love, on which the movie is based, ends with Bond “Feel[ing] his knees begin to buckle…Bond pivoted slowly on his heel and crashed headlong to the wine-red floor.”

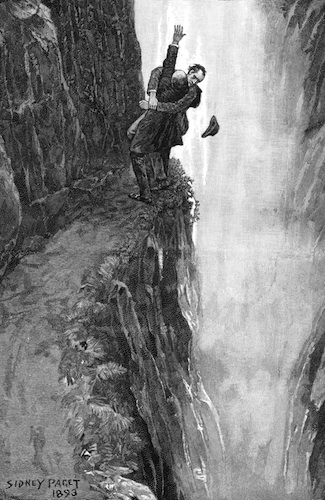

Really, Fleming wanted to stop writing the character and move on to other projects. He wasn’t the first author who grew tired of his iconic creation and tried to end him. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle tried to do the same to Sherlock Holmes, penning the short story “The Final Problem” in 1893 which saw Holmes face off with an abruptly introduced arch-nemesis and apparently die with him in the famous face-off at Reichenbach falls. Doyle wanted that to be the end of Sherlock’s adventures, because even though each story brought him a fat paycheck, he wanted the freedom to focus on more “serious” literary projects. “I think of slaying Holmes in the last and winding him up for good and all,” he wrote in a letter to his mother. “He takes my mind off better things.”

Really, Fleming wanted to stop writing the character and move on to other projects. He wasn’t the first author who grew tired of his iconic creation and tried to end him. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle tried to do the same to Sherlock Holmes, penning the short story “The Final Problem” in 1893 which saw Holmes face off with an abruptly introduced arch-nemesis and apparently die with him in the famous face-off at Reichenbach falls. Doyle wanted that to be the end of Sherlock’s adventures, because even though each story brought him a fat paycheck, he wanted the freedom to focus on more “serious” literary projects. “I think of slaying Holmes in the last and winding him up for good and all,” he wrote in a letter to his mother. “He takes my mind off better things.”

Fans, however, had other ideas. In 1901, Doyle bowed to the pressure and wrote The Hound of the Baskervilles, an adventure set before “The Final Problem.” But it wasn’t enough; in 1903 “The Adventure of the Empty House” recounts Holmes’ ‘miraculous’ survival at Reichenbach and return to England, and was followed by thirty-one more stories. Ian Fleming had no more success ending his hero as Conan Doyle; From Russia, With Love was but number five in twelve novels. And both Sherlock Holmes and James Bond outlived their creators; other writers have continued to pen, film and animate adventures for the characters, even into 2012, with Skyfall and the second season of the BBC’s Sherlock.

These are the most famous examples of extraordinarily long-lived characters, both within their own stories and in the pop culture zeitgeist, but very few others have seen the same success. Even the most beloved characters and stories outlive their welcome: Some TV shows like 24 or Supernatural, or manga like Naruto and Detective Conan, popular though they were (and still are), become infamous for running too long. Oftentimes, the accusation is that a work’s artistic integrity suffers when the creators try to forestall an ending. Other times, it simply becomes unbelievable that the characters are still alive. Resurrections, alternate timelines, and other tricks of the comic book trade aren’t as readily accepted here.

Canon, Fanon and Alternate Universes

The truth is, a story has to end sometime. And for those in the entertainment industry, when a story ends the money ends too. But the desire to turn a steady profit isn’t the only reason for the end of endings. Often, the people who drag out stories aren’t the ones who make money on them, but the ones who pay money for them. Sometimes these fan-driven projects involve the original creators, as with the multiple efforts successful and unsuccessful on the part of Firefly fans to resurrect the 2003 show. But most often they take it into their own hands. Yes, I’m talking about fanfiction. For some, consumption of fan-related content can outweigh the official material, not a difficult feat when multiple novel-length expansions, prequels, and alternative treatments of franchises like Harry Potter, Final Fantasy and Avatar: The Last Airbender are freely available online. Fan creativity has become a force to be reckoned with, and even a subject of study and scholarship.

The truth is, a story has to end sometime. And for those in the entertainment industry, when a story ends the money ends too. But the desire to turn a steady profit isn’t the only reason for the end of endings. Often, the people who drag out stories aren’t the ones who make money on them, but the ones who pay money for them. Sometimes these fan-driven projects involve the original creators, as with the multiple efforts successful and unsuccessful on the part of Firefly fans to resurrect the 2003 show. But most often they take it into their own hands. Yes, I’m talking about fanfiction. For some, consumption of fan-related content can outweigh the official material, not a difficult feat when multiple novel-length expansions, prequels, and alternative treatments of franchises like Harry Potter, Final Fantasy and Avatar: The Last Airbender are freely available online. Fan creativity has become a force to be reckoned with, and even a subject of study and scholarship.

Worlds without end

Why are fans able to continue stories that the writers had intended to be over? Why do they even want to?

It’s partly due to a shift in the way that we perceive fiction. Both fanfiction and videogames stem from an understanding of fiction as world-building, as the creation of a persistent imaginary realm that has past and future even beyond that which the narratives about it care to share. Worlds aren’t constrained by introductions, rising actions, climaxes, denouements and conclusions.

It’s partly due to a shift in the way that we perceive fiction. Both fanfiction and videogames stem from an understanding of fiction as world-building, as the creation of a persistent imaginary realm that has past and future even beyond that which the narratives about it care to share. Worlds aren’t constrained by introductions, rising actions, climaxes, denouements and conclusions.

Stories were always worlds first, but in the heyday of print and paper authors could regulate our access. The first chapters of books were our passports, the epilogues our deportation papers, and there was little we could do outside our own minds to linger in a beloved world. But now, not only are fans more able to rip open new holes in that curtain, due in part to mass media delivery technologies and accessible online publicatio – they’re encouraged to.

We don’t look at stories as linear narratives anymore. We look at them as excerpts from a longer and wider fabric, as portals into a persistent, if fictional, world. No longer do we experience stories as simple trajectories, as rides with a beginning, a middle, and and an end. Today, stories of all kinds come with sidequests, websites, mods, fanfiction communities, spinoff titles, miniseries and more. Between the “official” content and the fan-produced material, our fictional worlds have become functionally infinite.

Stories have endings, and will always have endings, but “the end” doesn’t mean what it used to mean. Maybe it never did. Because the worlds have no end.

———

Follow Jill Scharr on Twitter @JillScharr.